Let’s create some requirements

This is my second time around creating a portfolio from scratch. I had previously created a repository for and hosted my portfolio by using static HTML/JS/CSS and added some fanciness using special fonts, CSS Libraries, etc. I didn’t have as much of an eye for design, but, alas, I was young(er) and intrepid(er?), and every developer portfolio had ✨parallax scrolling background images✨ when I was looking at good examples of engineering portfolios, so that was the one killer feature I just needed to have.

Parallax scrolling feels like my “We didn’t start the fire” reference for this era of web development

I wanted to do a few things differently this time around:

- Create my portfolio while learning something new

- The portfolio website should facilitate creating a blog hosted at the same place (where fingers-crossed you’re reading this right now!)

- Keep things organized and give some assurances on what the site has

- Host my portfolio as cheaply as possible (thinking about it now, it probably should be my number one 😅)

Overall, I wanted to create something that was more dynamic but still had the simplicity of building a static site.

1. Learn some new stuff! 🎓

When building my portfolio this time around, I wanted to dive into file-based routing that I’ve heard about but haven’t used. Meta-frameworks like Next.JS, Gatsby, Remix, and Astro all leverage file-based routing, but I was intrigued by the notion of “Component Islands” in Astro and divorcing away from the reliance on a specific UI component library like React or Vue. Astro seems more like the UI-agnostic application framework, albeit by effectively creating their own UI component framework. That being said, I would argue their approach is essentially a simple abstraction of writing separate server and UI code and consolidating it in one place, while leveraging the benefits of modularity that you would get by creating the website in a component-based approach. To wit, it is UI-agnostic in that you can simply add an integration for your favorite UI component framework later on if you want.

---

import somethingCool from 'the-server-side';

---

<p>

{

`Hey everyone I get rendered on the server and displayed statically on the client and I can use ${somethingCool} from the server`

}

</p>

<script>

// I get sent to the client and run *strictly* on the client-side

alert('Yo what up client');

</script>

<style>

p {

/* This p tag auto-magically gets converted to a class-based rule using :where() when sent to the client*/

color: red;

}

</style>An example of an astro component. This is plug-and-play with whatever UI framework you want to use! 💪

Much like the advent of something like JSX, the utility in being able to marry server and client together into one file means that you can reduce the need to setup and manage a backend site for something simple like a static site, while still doing some complex things on the front-end so it’s not just a static site.

2. Create a blog 📝

My initial foray into creating a self-updating blog was to pull files from a gist and render the content on the screen. I eventually realized (read: actually looked through the documentation) that Astro provides some out-of-the-box support for stuff like blogs and other content via what they call “Content Collections”. An added benefit to content collections is that they allow for you to customize the layout of these content collections and how they are used, i.e. you can treat some content as a single page with a customized layout, or as an element on a page. On this site I used content collections for the blog (single page layout), the projects page (single page layout), and even the recommendations on the homepage (elements on a page). I quite like this because it makes it trivial to add or remove content and enable you to customize their rendering based on content type and not have to worry about each individual piece of content.

---

import BaseLayout from '../layouts/Base.astro';

import { request } from '@octokit/request'; // octokit/request is the GitHub API request library

// get all the blog posts from my public gist

const blog = await request('GET /gists/<my-gist-id>');

const posts: Object = blog.data.files; // pull the files (which are separate blog posts) from the gist

---

<BaseLayout title="Blog">

<main>

<h1>Blog</h1>

{

Object.entries(posts).map(([title, data]) => (

<>

<h2>{title}</h2>

<p>{data.content}</p>

</>

))

}

</main>

</BaseLayout>I spent a good 30 minutes thinking about the design of this and was super proud of coming up with this solution, only to find that Astro’s content collections make this 10x easier. 🚀

Obviously reading documentation and understanding what a framework offers is paramount to maximizing the value you get from using it, but what I went through speaks to a mindset of not needing to start from scratch. This is something that I think a lot of developers have to learn and relearn.

3. Keep it clean 🧼

To me, cleanliness of a project is mostly about being able to find what you need when you need it. Organization is key and being able to modularize things as much as possible allow for you to piece together a project like building a lego and the organization (and especially the documentation) of a project should allow just about anyone to jump in and understand what’s going on with as little effort as possible.

Thankfully, the file-based nature of Astro lends itself to keeping things organized, but I did run into some issues while creating this portfolio in establishing some global style rules. Last time around I had used a self-hosted, minified version of MaterializeCSS, and made minor tweaks on top of that by creating a custom stylesheet that would be used across the site. This allowed me to really focus on cooler things like parallax images (heh) and a fun layout for my resume and create a custom timeline layout by using a bunch of divs and the materialize layout grid (this was before things like CSS Grid):

Evidently, I really like card-based design for projects

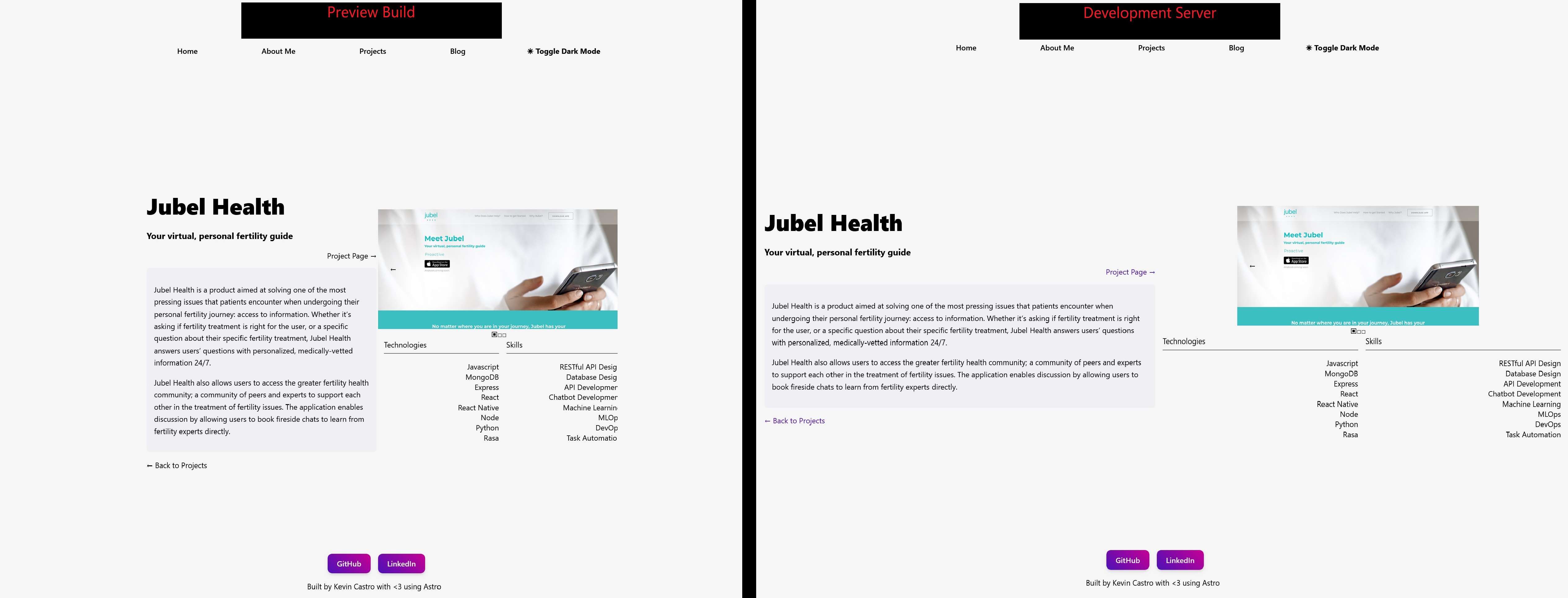

However, this time I wanted to use as little customized CSS styling as possible. Astro does not come with any default styling, so I created some styles I wanted to be consistent across all pages by creating a base layout with some global styles. Problem is, the way these styles are imported at build time led to some inconsistency between the dev server and how the resulting preview build looked:

Yes, I made this screenshot in MSPaint and no, I won’t say sorry.

Once I reduced some of the tag-based global styles and moved to more class-based stylings, which is their recommended styling methodology, this was fixed, but I think is one of the pain points in using Astro; this could definitely be a case where I didn’t understand how these imports worked, but I would argue that inconsistencies between dev and the resulting build should be minimized as much as possible.

4. Host everything on the cheap 💸

Before the advent of product offerings like GitHub Pages, folks in the before times (a.k.a. like 4 years ago) needed things like Wordpress or what I used before which was Google’s Firebase to host static pages cheaply. A huge reason for me choosing Astro was that it had some built-in support for deploying and hosting the page on GitHub pages. Setting up Continuous Deployment (the CD of CI/CD) was quick and painless using their GitHub Action. The only real tricky part of this process was setting up the DNS records in a way that allowed for me to setup the GitHub Pages to point to the Apex Domain. It’s a bit counter-intuitive, but setting up a www subdomain and the A records to the IPs they prescribe allowed for me to host the site on https://kevincastro.dev while allowing for the necessary redirects to happen in the background.

In any case, it definitely feels like Astro and industry tooling nowadays means developers can setup hosting easily. To some degree, I think the industry at large has refocused away from trying to capture developers trying to host sites as paying customers to the Freemium model whereby they offer a free-tier as an entrypoint, helping convert the developers as evangelist for their platform’s offerings. It’s a win-win for developers like myself working on side projects and the platforms that enable this kind of hosting. Fingers crossed this model persists in the future and allows for some more experimentation with other hosting solutions down the line.

Let’s recap

Let’s review the current state of the art: the move to developer-friendly frameworks, free or low-cost hosting, and the impact of UI component libraries means that building websites nowadays is more successful and less error-prone. There are still pitfalls that your typical developer might fall into in the development process, but on the whole it seems like the tools are now suited to the developer and not the other way around. Web development is still messy; it’s a cacophony of server-side business logic, client-side weirdness, and custom-built functionality that glues everything together. However, the improvement in only 4 years is leaps and bounds greater than what I think has happened in other areas of software development. It’s the fast-improving but ever-changing landscape which is in part because of the many touch points that web development has across a product vertical. Websites are expected to capture customers, deliver value, and interface with critical business components so as much as I would like to build out a “perfect” website, I also understand that it’s an organic thing that is constantly evolving. My portfolio might change entirely in the coming years, because the purpose or need I have for this website changes for the furthering of my career, and that’s ok. The work I’ve put into this site is not for naught, but for the specific needs I have at this point in time. I just hope that by the time I need to repurpose this site, things have improved even more.